The first coachbuilt Rolls-Royce orchestrated by Ayrspeed has now been completed and delivered to Chicago.

The 1950 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith rolling chassis had been around for a while, with a Weymann-style open touring ash and fabric body planned for it. The Wraith project was then pushed out of the way by a Bentley special, a MkVI parts car rescued and fitted with an aluminium boat-tailed body inspired by Type 35 Bugattis admired at French vintage racing events. This was a fascinating sculptural exercise, but did not end up as a beauty. The big vintage Phantom-style RR tourer was still the ultimate aim, and the Bentley was a sidetrack.

The surplus-to-requirements Bentley special was mentioned in a story in the RROC club magazine and put up for sale, to see if any other club member might want to take it on and finish it. Al Levit in Chicago read the story, which featured a drawing by Vancouver designer Brian Johnston. Al fell in love with the boat-tailed speedster idea, and asked if he could buy the Wraith chassis as well as the Bentley’s boat-tailed body, and also asked if he could commission Ayrspeed to build the car as a 1930s-style Rolls-Royce speedster, using Brian’s sketch for inspiration where that was practical. Brian had created an artist’s impression rather than a functional design drawing.

Did Iain want to sell his Rolls chassis with the Bentley body and build a big, spectacular, unique, properly funded motor car? Excellent idea, let’s do that. Ayrspeed the design company rose from its slumber, and conceptual thinking and sketching commenced.

The choice of craftsman for the mechanical, chassis and body frame work was Adam Trinder of AMTMachine.com, who was chosen because of clever, elegant, creative, economical work displayed in a Mini he had built with a bike engine in the back seat. He had retained both the Mini rear subframe and a fully functional boot space, and he offered a full machine shop and good engineering skills.

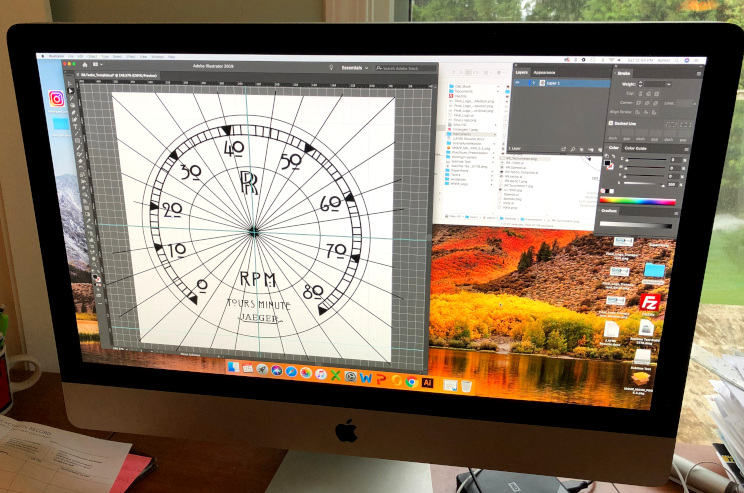

The original 4¼-litre Rolls engine came with the Silver Wraith, but in 1950 these engines still had design faults, and this one had not been rebuilt. It will remain with the car, but it has been replaced in the engine bay by the biggest and best of the postwar RR and Bentley straight sixes: in the final 4.9-litre Silver Cloud incarnation of the engine from 1955 to 1957, all the issues have been ironed out, and its power and torque are certainly “adequate”. This particular 4.9 engine was rebuilt by Tom Mellor, Vancouver RROC tech consultant, who has persuaded a 1970s Triumph Trident motorcycle to top 200mph at Bonneville. So he knows whereof he speaks.

With the team of contractors in place, the orchestration of the car began. It was designed with only basic sketching and with no computers, initially by mocking up shapes and parts in Iain’s garage, and then for real in Adam Trinder’s workshop, by the simplistic but reliable method of doing it by doing it.

There are rules for vintage car design.The front axle must be on or behind the front axle line. The bonnet must tilt down at the front by 1-3 degrees. An Ayrspeed rule is that the car must be genuinely drivable for long-distance use, so the seat has to be both a proper car seat and mounted high enough for a proper driving position. Most low flat-floor Bentley specials fail in this. We sit on a milk crate or box on the chassis, and move it around until its position on the car feels right. Then we stand back and look at the driving position and thus where the cockpit and doors will be. Is the relationship between the longish front of the car and the less long back of the car pleasing? Move the crate (and the future cockpit) back and forth to find the optimum position.

The chassis of the Wraith is 7” longer than the MkVI Bentley. It’s a little too long for a two-seater, but Al previously had a bad hip, now successfully restored, and we needed to design in long doors that could be leaned on, so we made it work. Iain also nipped a little off the back of the chassis. We balance the car’s height against its length: the higher it is, the less over-long the tail will look. We know the minimum height of the car’s body, dictated by the seats. Its final height is a visual judgment call.

Make the judgment; Adam measures where Iain’s hand is, tacks some steel in place, job done. Adam also cut the bulkheads and, delightfully, cut down the heads of the front bulkhead’s securing bolts in a lathe so that they looked like big rivets. Okay, that is much of the base design achieved. The gear lever has to be where Al’s hand expects to find it, and that, combined with the radiator position and a semi-rule that you ideally move the engine towards the centre of the car to reduce its polar moment of inertia, dictates the ideal engine position as well. Gear levers can be slightly angled, but we don’t want a weird unnatural shift action. The steering wheel must also please and must fall to hand, so the steering box is repositioned on the chassis, and the angle of the steering column is set. The milk crate comes out again for that. The radiator’s position is dictated by the front axle line rule, but its height is now fixed – it’s an inch below the centre of the main bulkhead. If the engine is here, the pedals need to be here, although luckily they’re Rolls-Royce pedals so the pads are adjustable by a few inches. The rear bulkhead position is more flexible, but the cutaways on the suicide doors must have a pleasing curve, and the suicide doors will hang from the rear bulkhead. The cutaways have to be low and sexy enough to please Al, but not so low that they scare his wife with the road visibly whizzing past.

As the shapes of the body frame design themselves, Adam Trinder is tacking steel body tubing in place with Iain, then later finish-welding it all in position, while Iain comes by a few times a week to steer the project and to fit the car to himself – luckily he’s the same size as Al, so if the car fits the designer it will fit the owner. A car has to be drivable by both Kylie Minogue and Jason Momoa, so there has to be full adjustability in the driving position. The Wraith has enough flexibility in the seat rails and backrest bracing and pedals for any size person to drive the Wraith: this turned out to be wise, as Al’s wife Lana also loves this car and will be learning to drive a manual gearbox so that she can enjoy it.

One excellent innovation for Ayrspeed and for Al has been the Sunday report. Every Sunday evening, Iain sits down with a glass of Laphroaig and writes Al a report on the week’s progress. This creates discipline. It makes sure Iain doesn’t get sidetracked and keeps his eye on the ball, it means at least one weekly physical visit to the car to take photos to send, and a discussion of progress with the relevant craftsman. It also imposes a regular time to stand back and look at the project, and helps to keep a firm grip on all aspects of the build. The chassis visibly wears some of its history: it is a real post-vintage coachbuilt Rolls getting a new body, and we’re not pretending otherwise.

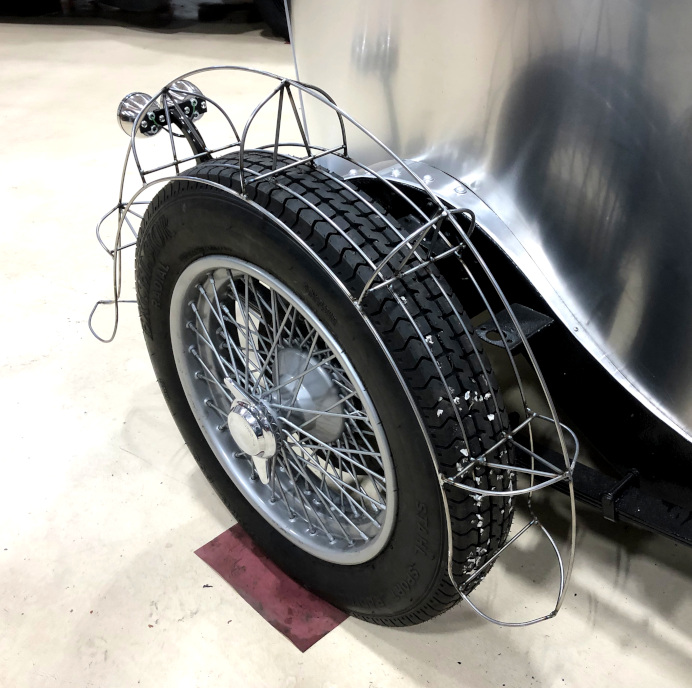

With the main structure and bones of the car finished, the Wraith was drivable and after brief winter road testing, the skinning of the frames and chassis began. The direction of the project then changed, and the cost and timescale quadrupled. From a cool speedster, it evolved into a world-class 1930-styled show car valued by Hagerty at half a million dollars. One of the brutally expensive but worthwhile decisions was to replace all the chrome plating on the car with nickel: its warm colour changes the whole visual feel of the car, and locks it in the period as well.

This upscale change of direction was a conscious decision made with Al the owner, and the end result approached perfection, until the body contractor amputated the front apron and faux chassis horns at the front of the car, and the paint colours went wrong. The mistakes will be corrected in Scotland ready for the car’s eventual formal debut on the Ayrspeed stand at Retromobile in Paris.